Friedrich Nietzsche showed an interest in music from a young age, composing pieces for piano, orchestras and choirs. In his teens, he spent his summers leading “a small music and literature club named ‘Germania,'” and was exposed to Richard Wagner’s music through it.

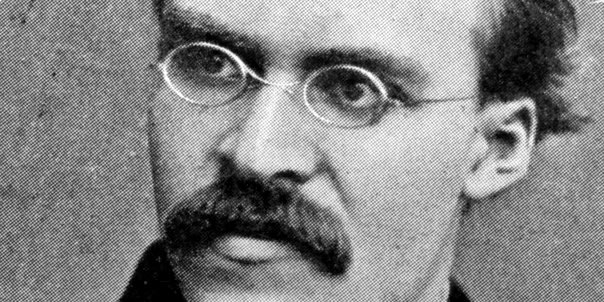

Above is Nietzsche’s “Manfred Meditation,” a piano piece written for four hands. It is also subject to one of the most scathing reviews Nietzsche ever received in his lifetime.

Nietzsche, in his philosophical work, frequently invoked music and art. He famously declared that “Without music life would be a mistake,” in Twilight of the Idols. Later in his life, he wrote “The Case of Wagner,” a piece of music criticism.

Much of Nietzsche’s music compositions have since been performed, recorded and distributed online. That includes the complete array of his piano works performed by Michael Krucker and another compilation that includes his choral pieces and piano pieces performed by Lauretta Altman.

Most of the music was written between the ages of 13 and 22. If you have Spotify, you can listen below, although much of it is also available on YouTube.

But Nietzsche wasn’t without critics, after sending one of his pieces (in the video above) to celebrated composer Hans von Bulow, he received this damning and cruel criticism:

But to the matter at hand: your Manfred-Meditation is the most extreme case of fantastic extravagance, the most unedifying and anti-musical instance of notes placed on music paper that I have come across in a long time. Several times I had to ask myself: is the whole thing a joke, and did you perhaps intend a parody of the so-called music of the future? Did you consciously flout all the rules of musical language, from the higher syntax to simple matters of correct notation? Apart from the psychological interest—your musical fever-product gives evidence, despite all the confusion, of an uncommonly distinguished spirit—your Meditation is from the musical standpoint the equivalent of a crime in the moral world. I could discover no trace of Apollonian elements, and as for the Dionysian, to be frank, I was reminded more of the morning after a bacchanalian orgy than of an orgy per se. If you really have a passionate urge to express yourself in musical language, it is indispensable that you acquire the rudiments of this language: giddily fantasizing on a remembered gluttony of Wagnerian sounds is no basis of production.

It should be noted, that Bulow knew very well who Nietzsche was. In the beginning of the letter he praises him as a “scholar of creative genius.” Nietzsche continued a friendly letter exchange with Bulow after the fact and apologized “for his alleged musical crime,” according to Alex Ross.

[H/T Open Culture]