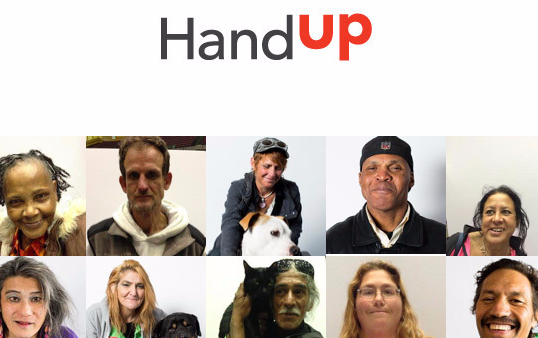

Frame after frame of smiling weather-beaten faces stare out at us, their tired contours captured in beautiful high definition black and white. This is the website of HandUp, a recently founded charity in San Francisco, offering what is in effect the opportunity to “adopt a homeless”. What does this form of giving that requires no actual physical encounter with that dangerous object “the homeless person” tell us about the middle class’s developing relationship to poverty?

Handup is designed to get around our wariness that the people who beg from us on the street will simply spend what we give them on drugs and alcohol. Homeless people register with the company and instead of begging, hand out business cards to passersby, encouraging them to read their stories online and – if moved to – donate money that is then converted into credits for food, clothes and medical supplies. The scheme has all the strengths of the American West Coast: smart but intuitive, satisfying in its finding in modern technology solutions for age-old social problems, and humanely committed to the therapeutic ideal that everyone has a story to tell. Clearly HandUp does the recipients of its online visitors’ largesse a great deal of good: but there is also something deeply troubling about the strategy of this latest means by which we are invited to encounter the poor.

Animal welfare charities have long employed a very similar marketing approach. Rather than simply making a donation to the World Wildlife Fund or to the Born Free Foundation, donors “Adopt an Animal” – Kamrita the Bengal tiger for instance, or Springer the whale – and receive regular updates about that animal’s particular activities and progress. In the meeting of these two approaches to charity, we are as so often treating humans like animals and animals like humans, but with one key conceptual difference. In the Adopt and Animal strategy, the cute marketable Panda presents one anthropomorphised animal in particular on whom donors can focus their sense of having done good, while the proceeds themselves go to help the species at large. In the Handup model however, the homeless people with the most inspiring story and the most effective combination of pathos and defiance in their photograph benefit personally, while those with problems less marketable in the online arena get nothing.

The implications of this can be drawn out with reference to the philosopher Alenka Zupančič’s notion of “bio-morality”. Zupančič suggests that in the past, the Left has only had to respond to the “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” model of conservative morality, for which social misfortune is ultimately the result of idleness and poor decision making. The situation of bio-morality meanwhile has gone yet further, promoting the view that “feeling good” and “seeing the positive” are markers of moral goodness in themselves, intimately related to social status, and inscribed at the level of a person’s biology. This is what has allowed healthy eating and exercise to take on the status of a moral virtue, and one explicitly linked to getting ahead. As such, the supposed enjoyment of junk food and cigarettes among the unemployed becomes imaginatively intertwined with their social predicament, making it seem like poverty was always inscribed biologically. The ease with which antidepressant drugs are now prescribed in the West is also part of this trend: unhappiness is presumed to be always biological, and the only socially responsible reaction to it is to chemically change our biology. And this is also why we are now encouraged to reformulate all misfortune into a “learning experience”, a welcome challenge, or as a near miss with some even worse fate. In the bio-moral regime, to be conspicuously unhappy or sickly without finding some source of positive inspiration inside that is to risk the perception that we had it coming.

This is the responsibility HandUp imposes on its clients: the responsibility to prove their worth at the level of bio-morality. Whether to become a child psychologist, to start crochet classes for other indigent people, or to find work as a mechanic, all the narratives given on the website include some inspirational dream or ambition. At the same time, the classy portrait photographs show good-humoured, kindly, basically healthy-looking people. In other words, the kind of people for whom misfortune is a temporary episode in an otherwise positive story, and not the kind of people who are damned to unhappiness by a knot of bad morals, bad luck, and bad biology at the heart of their being.

The inspiring stories are an undoubted part of the website’s pull, which together with the assurance that the donations will only be spent on “the right” things, allow us to see the effects of our charity. But clearly there is an intellectual glitch here as well. What HandUp seems to offer is an approach to the homeless that allows them to speak for themselves in all the variety of their experience. But its effect is to encourage us to donate to the client whose ambitions and experiences most resonate with our own. While it is their apparent uniqueness that draws us to the homeless person we sponsor, the result is only that we normalize and impose our own priorities back onto them. There is a reason why the animal charities market “adopt an animal” to children: it is because to be willing to offer help to the Other only when he or she appears in a reassuringly identifiable and upbeat form is a childish ethics indeed. To allow ourselves to associate deservingness not only with need, but with a constitutionally positive attitude with which we can presume to identify, is a dangerous habit of thought to be getting used to.