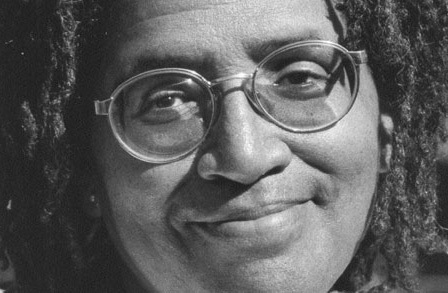

Audre Lorde (February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) would have turned 79 today. The poet and activist was an outspoken critic of feminism’s focus on white, middle-class, heterosexual women by invoking the intersections of race, class, gender and sexuality (before it was cool).

Her legacy has been cemented by the The Audre Lord Project, an eponymous community organizing network for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Two Spirit, Trans and Gender Non Conforming People of Color.

Below Lorde argues in her seminal essay “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” argues against white feminist academics who are unwilling to cope with the fact “that the women who clean your houses and tend your children while you attend conferences on feministtheory are, for the most part, poor women and women of Color.”

Read the entire essay below:

I agreed to take part in a New York University Institute for the Humanities

conference a year ago, with the understanding that I would be commenting

upon papers dealing with the role of difference within the lives of American

women: difference of race, sexuality, class, and age. The absence of these

considerations weakens any feminist discussion of the personal and the

political.It is a particular academic arrogance to assume any discussion of feminist

theory without examining our many differences, and without a significant

input from poor women, Black and Third World women, and lesbians. And yet, I

stand here as a Black lesbian feminist, having been invited to comment

within the only panel at this conference where the input of Black feminists

and lesbians is represented. What this says about the vision of this

conference is sad, in a country where racism, sexism, and homophobia are

inseparable. To read this program is to assume that lesbian and Black women

have nothing to say about existentialism, the erotic, women’s culture and

silence, developing feminist theory, or heterosexuality and power. And what

does it mean in personal and political terms when even the two Black women

who did present here were literally found at the last hour? What does it

mean when the tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of

that same patriarchy? It means that only the most narrow perimeters of

change are possible and allowable.The absence of any consideration of lesbian consciousness or the

consciousness of Third World women leaves a serious gap within this

conference and within the papers presented here. For example, in a paper on

material relationships between women, I was conscious of an either/or model

of nurturing which totally dismissed my knowledge as a Black lesbian. In

this paper there was no examination of mutuality between women, no systems

of shared support, no interdependence as exists between lesbians and

women-identified women. Yet it is only in the patriarchal model of

nurturance that women “who attempt to emancipate themselves pay perhaps too

high a price for the results,” as this paper states.For women, the need and desire to nurture each other is not pathological but

redemptive, and it is within that knowledge that our real power is

rediscovered. It is this real connection which is so feared by a patriarchal

world. Only within a patriarchal structure is maternity the only social

power open to women.Interdependency between women is the way to a freedom which allows the I to

be, not in order to be used, but in order to be creative. This is a

difference between the passive be and the active being.Advocating the mere tolerance of difference between women is the grossest

reformism. It is a total denial of the creative function of difference in

our lives. Difference must be not merely tolerated, but seen as a fund of

necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a

dialectic. Only then does the necessity for interdependency become

unthreatening. Only within that interdependency of different strengths,

acknowledged and equal, can the power to seek new ways of being in the world

generate, as well as the courage and sustenance to act where there are no

charters.Within the interdependence of mutual (nondominant) differences lies that

security which enables us to descend into the chaos of knowledge and return

with true visions of our future, along with the concomitant power to effect

those changes which can bring that future into being. Difference is that raw

and powerful connection from which our personal power is forged.As women, we have been taught either to ignore our differences, or to view

them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for

change. Without community there is no liberation, only the most vulnerable

and temporary armistice between an individual and her oppression. But

community must not mean a shedding of our differences, nor the pathetic

pretense that these differences do not exist.Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society’s definition of

acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of

difference — those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who

are older — know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how

to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common

cause with those others identified as outside the structures in order to

define and seek a world in which we can all flourish. It is learning how to

take our differences and make them strengths. For the master’s tools will

never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat

him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine

change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define

the master’s house as their only source of support.Poor women and women of Color know there is a difference between the daily

manifestations of marital slavery and prostitution because it is our

daughters who line 42nd Street. If white American feminist theory need not

deal with the differences between us, and the resulting difference in our

oppressions, then how do you deal with the fact that the women who clean

your houses and tend your children while you attend conferences on feminist

theory are, for the most part, poor women and women of Color? What is the

theory behind racist feminism?In a world of possibility for us all, our personal visions help lay the

groundwork for political action. The failure of academic feminists to

recognize difference as a crucial strength is a failure to reach beyond the

first patriarchal lesson. In our world, divide and conquer must become

define and empower.Why weren’t other women of Color found to participate in this conference?

Why were two phone calls to me considered a consultation? Am I the only

possible source of names of Black feminists? And although the Black

panelist’s paper ends on an important and powerful connection of love

between women, what about interracial cooperation between feminists who

don’t love each other?In academic feminist circles, the answer to these questions is often, “We

did not know who to ask.” But that is the same evasion of responsibility,

the same cop-out, that keeps Black women’s art out of women’s exhibitions,

Black women’s work out of most feminist publications except for the

occasional “Special Third World Women’s Issue,” and Black women’s texts off

your reading lists. But as Adrienne Rich pointed out in a recent talk, white

feminists have educated themselves about such an enormous amount over the

past ten years, how come you haven’t also educated yourselves about Black

women and the differences between us — white and Black — when it is key to

our survival as a movement?Women of today are still being called upon to stretch across the gap of male

ignorance and to educate men as to our existence and our needs. This is an

old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with

the master’s concerns. Now we hear that it is the task of women of Color to

educate white women — in the face of tremendous resistance — as to our

existence, our differences, our relative roles in our joint survival. This

is a diversion of energies and a tragic repetition of racist patriarchal

thought.Simone de Beauvoir once said: “It is in the knowledge of the genuine

conditions of our lives that we must draw our strength to live and our

reasons for acting.”Racism and homophobia are real conditions of all our lives in this place and

time. I urge each one of us here to reach down into that deep place of

knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any

difference that lives there. See whose face it wears. Then the personal as

the political can begin to illuminate all our choices.