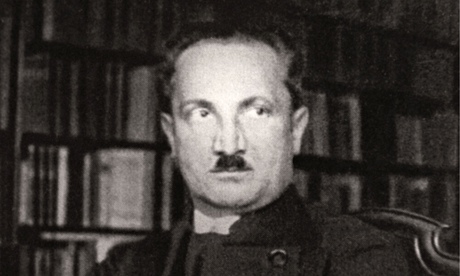

Nearly 40 years after his death, the debate still rages on concerning Martin Heidegger’s Nazism. The German writer of “Being and Time” and “The Question Concerning Technology” has left a huge impact on what we now know as critical theory. Writers like Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault all considered the German philosopher’s work extremely important, Foucault even remarked that Heidegger was foundational to his philosophical development. But “The Black Notebooks”, a new German publication of Heidegger’s work, is allegedly putting the debate to rest. Heidegger was probably a pretty big Nazi, and at the very least, probably didn’t like Jews that much.

Previously, both sides of the argument had some fairly compelling points. The pro-Heiddeger camp employed the “he had a black Jewish friend” defense and pointed to his romantic relationship with Hannah Arendt, noted Jewish philosopher and also, creepily enough, his student. Arendt also came to Heidegger’s defense when he was going through the post-war de-nazification process. Heidegger was ultimately labeled a “band-wagoner” and allowed to return to teaching later in his life.

On the anti-Heidegger side of the debate, there also exists some fairly damning evidence. Exhibit A) He was actually a member of the Nazi Party. He was also promoted to be the Rector of the University of Freiburg at a time when being in charge of a university meant being ideologically aligned with the Nazi Party. But while Heidegger was tangled up in all sorts of Nazi business like denying Jews financial aid and purging faculty who weren’t “Nazi enough,” he also stopped book burnings and later claimed, essentially, that it was better that he be in charge rather than a bonafide “real” Nazi. Most of the charges of Heidegger’s personal anti-Semitism have been anecdotal. As The Guardian notes, there is no definitive “smoking gun,” until now.

“The Black Notebooks,” which some Heidegger scholars tried to stop the publication of, provides strong evidencethat his philosophical thought has been colored with anti-Semitism.

As Slate writes:

Before he died, Heidegger dictated the exact order his unpublished works should appear, and the Black Notebooks, three leather-bound volumes he kept during the 1930s and ’40s, will finally be published in German later this month. Although they are officially embargoed until publication, their editor, University of Wuppertal professor and director of the Heidegger Institute Peter Trawny, has discussed their content with the press. Further, several excerpts, slated to appear in Trawny’s own forthcoming book, have leaked—and, as Hockenos puts it, they “seem to illustrate beyond a doubt that Heidegger harbored anti-Semitic convictions during the Nazi dictatorship.”

Heidegger used terms like “world Judaism” and claimed it was a driving factor in modernity, a term The Guardian attributes to the anti-Semitic “Protocols of the Elden of Zion.”

The notebooks also show that for Heidegger, antisemitism overlapped with a strong resentment of American and English culture, all of which he saw as drivers of what he called Machenschaft, variously translated as “machination” or “manipulative domination”.

In one passage, Heidegger argues that like fascism and “world judaism”, Soviet communism and British parliamentarianism should be seen as part of the imperious dehumanising drive of western modernity: “The bourgeois-Christian form of English ‘bolshevism’ is the most dangerous. Without its destruction, the modern era will remain intact.”

Also in the notebooks:

“World Judaism”, Heidegger writes in the notebooks, “is ungraspable everywhere and doesn’t need to get involved in military action while continuing to unfurl its influence, whereas we are left to sacrifice the best blood of the best of our people”.

But while plenty will be quick to urge the abandonment of Heidegger’s work in philosophy class, his anti-Semitism doesn’t seem any more egregious than Aristotle’s robust defense of slavery, the overt racism of many Enlightenment thinkers, or Plato’s proto-fascist douche-baggery. If anything, it’s a reason that philosophy students should be wary when engaging with Heidegger in the same way we are (hopefully) wary of the rest of philosophy’s terrible canonical figures. None of the available English journalism on the German text cites any example of Heidegger supporting the Holocaust, the genocide of the Jews, or any other victim of the Holocaust.

That being said, the question should be asked: are there any of Heidegger’s ideas that are inextricable from Nazism? Maybe, and it’d probably make for some great scholarly work. But that answer probably isn’t “all of it.”

But scholars (who are most certainly not Nazis) have re-imagined Heidegger’s work regardless of the author’s original intention. William V. Spanos, for instance, has leveraged the work of Heidegger to argue against the racist imperialism of the United States. And the fact that Jewish scholars like Hannah Arendt and Jacques Derrida employ his work for explicitly anti-totalitarian purposes probably is proof that his work can be divorced from its original intentions.

Read the full story on The Guardian.